The beginning of the 2000s brought to a head a number of issues that had been simmering throughout the 1990s around the participation of young people in youth arts and in the arts in general. A sense of balance and inter-generationalism was to be at the core of Lowdown’s new editorial policy, and corresponded with a number of changes taking place around the country. Little were Lowdown staff to know this new focus on a ‘next generation’ in Australian youth arts was to help make Adelaide, once again, the centre of world youth arts in 2008.

Living Journeys 1979-2000 - Lowdown's 21st birthday issue

Lowdown celebrated its 21st birthday by celebrating Australian youth performing arts, profiling a longstanding company or organisation in every State and Territory. They were Carclew (SA), Barking Gecko Theatre Company (WA), PACT Youth Theatre (NSW), Jigsaw Theatre Company (ACT), Backbone Youth Arts (Qld), Arena Theatre (Vic), Corrugated Iron Youth Arts (NT), Salamanca Theatre Company (Tas) and Spare Parts Puppet Theatre (WA). (WA managed to sneak in two companies!)

The theme was ‘Living Journeys’, and the issue looked at how the youth performing arts had responded to the challenges and changes of the previous twenty-one years.

Together with some thoughts from AYPAA and YPAA luminaries, along with past Lowdown editors, the issue also explored some of the unique characteristics of Australian youth performing arts.

Feeding the Theatre Animal - training in youth arts, 2000

By 2000, the demise of the BA in Drama Studies at the University of Adelaide, the Drama Dip Ed at Rusden College and Melbourne State College in Victoria and the emergence of interdisciplinary courses at TAFEs and universities reinvigorated the debate about generalist versus specialist training in theatre. Many prominent practitioners in performing arts had trained in generalist courses – originally teacher training courses that had been absorbed into the university system and then closed. In South Australia these include Chris Drummond (Brink), Andy Packer (Slingsby), Michael Hill (Come Out) and Sasha Zahra (Adelaide Fringe).

With professional work dependent on a range of theatre skills, Jane Woollard questioned whether current arts training was actually undermining the ability of graduates to survive, and for contemporary Australian theatre to thrive.

Best Practice in Youth Arts? Danielle Cooper, 2000

Youth arts companies need to be assessed on process as well as product. But what mechanisms can be put in place to achieve this, and how do funding bodies determine best practice? Lowdown Editor Tony Mack commissioned Danielle Cooper to explore this topic in 2000.

The Australia Council Youth Panel, 2001

Established in October 1999, the Australia Council Youth Panel was let loose within the Australia Council to ‘articulate the needs of young people, to advocate for them, and to improve access for young people by bringing their informed ideas to Council’. (Youth and the Arts Framework, ‘ 1999).

The Panel attempted to raise a range of issues and offer suggestions to increase awareness about young people’s participation in the arts, and embed long-term change within the Council.

As the Youth Panel entered its last days, Lowdown asked Panel members Lana Gishkariany and Karen Bryant to reflect on the achievements of the Panel and the challenges ahead, and also published responses to the article from Ruth Osborne (ACT), Ryk Goddard (Tas), Tony Le Nguyen (Vic) and Jane Neville (WA).

Theatre for Young People in Australia - Judith McLean & Susan Richer, 2001

Judith McLean and Susan Richer’s paper ‘Theatre for Young People in Australia’ sought to provoke and prompt discussion on theatre for young people for the Theatre Board of the Australia Council in early 2001. The paper’s four provocations give an insight into the rigour of the thinking in Queensland at the time, implemented in programs like the Out of the Box Festival and the projects of Youth Arts Queensland.

The 2002 ASSITEJ World Congress in Seoul, Korea

Lowdown once again reported from an ASSITEJ World Congress in 2002, this time in Seoul, Korea. The Lowdown coverage also included an interview with Park Myung Shin, the owner of the large English language learning company Unibooks, and Carol Wellman from WA’s Buzz Dance Theatre, which was invited to perform as part of the official Congress program. Park Myung Shin was financing LATT Children’s Theatre, headed by REM Theatre’s Roger Rynd from Australia.

At this Congress Tony Mack, the Lowdown Editor at the time, was elected to the Executive Committee of ASSITEJ and returned to Australia as an ASSITEJ Vice-President, a position he would hold for six years. During that time, the travel and connections made through the ASSITEJ network dramatically increased the magazine’s ability to source articles from anywhere in the world.

The Theatre for Young People Review, 2002

In September 2002 the Theatre Board of the Australia Council decided to undertake a national review of Theatre for Young People. The NSW Ministry for the Arts had approached the Australia Council with the idea after a series of funding cuts to NSW companies – REM Theatre lost federal funding in 2001, as did Theatre of Image in 2002, and Freewheels, based in Newcastle, had its funding halved.

The Australia Council found it was funding performance for young audiences $600,000 less than it was a decade before, and was still relying for policy in the area on the notes from the December 1991 Performing Arts Board meeting that were harshly critical of work for young audiences and effectively announced the end of federal funding for Theatre in Education (TIE). Lowdown communicated, in the pages of the magazine and in discussions with the Australia Council, that the idea of no federal theatre funding for the adult audiences of Sydney would be an outrage. So why were the children of Sydney less important?

Jane Woollard examined the NSW cuts, the McLean/Richer paper and other issues in ‘Reviewing Theatre for Young People’.

An Audience with the Audience - Chris Thompson, 2003

Melbourne writer Chris Thompson interviewed, in 2003, young people who were attending theatre to find the answers to questions such as:

- Do young people think of themselves as young people?

- Do they think of themselves as young audiences?

- Do they care whether a performance is made specifically for or by young people?

He also talked with companies about how they viewed their relationship to their audiences.

Kosova's Dodona Theatre for Children and Youth, 2004

In 2004, Lowdown commissioned Kosovo playwright Jeton Neziraj to write the feature ‘Kosova’s Dodona Theatre for Children and Youth – The Muse of Resistance’. Detailing, for the first time, the activities of the theatre under the Serb occupation, the impact of the NATO bombing campaign, the expulsion of the staff of Dodona along with a million Kosovars from their country and the performances of plays by Dodona actors in refugee camps, the story has been re-published in the USA, UK and on numerous blogs and website.

Reference, Assemblage and Interactivity - Dave Brown, 2004

The Artistic Director of SA’s Patch Theatre, Dave Brown, outlined his approach to creating new work for children in this 2004 Lowdown article.

Lowdown in the Middle East - Jordan, 2004

In April 2004 Lowdown Editor Tony Mack represented Australia at a meeting of ASSITEJ, the international association of theatre for children and young people, in Amman, Jordan.

Arriving at a time of tension for this troubled region – in neighbouring Iraq Western contractors were fleeing the country after numerous killings, there were car bombs in Amman upon his arrival, and the leader of Hamas had just been assassinated a short distance away in the Occupied Territories – he found Jordan a far different country to how it may be perceived outside the Middle East.

Zen and the Art of Selling Shows - Kim Peter Kovac, 2005

Come Out, Young People and the Arts Australia and the Australia Council’s Audience and Marketing Development Division teamed up in 2005 to create a two day series of pitches to a group of international presenters from the US, Japan, Korea, and Brazil that included Kim Peter Kovac, Masami Miyashita, Luiza Monteiro, Hisami Shimoyama, and Kim Woo Ok. As Director of Youth and Family Programs at the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, Kim Peter Kovac had been on the receiving end of numerous pitches from TYA (Theatre for Young Audiences) companies in the US. Finding that Australian companies were still unused to pitching their work for international presenters, Lowdown convinced Kovac to put down some tips on paper.

The article was re-published the US and used as a discussion paper for the Mid-Atlantic Arts Conference in the USA in 2006.

Australia at the 2005 ASSITEJ World Congress in Montreal

The SA Minister Assisting the Premier in the Arts, John Hill, was part of the Australian delegation to the 2005 ASSITEJ World Congress in Montreal. He was supporting a very strong bid organised and led by Carclew Director Jessica Machin, to once again host an ASSITEJ Congress in Adelaide, this time in 2008. Lowdown Editor, YPAA Board member and ASSITEJ Vice-President Tony Mack had been lobbying for votes on all continents in the previous months. Adelaide was awarded the 2008 Congress and Mack, as ASSITEJ Vice-President and Chair of its Congress Working Group, was given the responsibility for the delivery of the Congress.

During the Congress NSW company Zeal Theatre was awarded the prestigious ASSITEJ Honorary Presidents’ Award for Excellence.

The Theatre Board's 'Make It New' discussion paper, 2006

Released on 1 May 2006, this discussion paper from the Theatre Board of the Australia Council for the Arts put forward a range of proposals affecting the funding of theatre throughout the country. It stimulated nationwide discussion and significant changes to funding categories and processes. Ironically Lowdown, which helped to initiate debate on the ‘Make It New’ paper in the youth arts sector, did not eventually fit into the new funding categories.

Australia at New Visions/New Voices, Washington DC, 2006

The New Visions/New Voices Festival of New Works for Young Audiences, at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC, is a key event in youth performing arts in the country. Previously an all-American affair, Lowdown Editor Tony Mack facilitated discussions between the Australia Council and Kim Peter Kovac, the co-founder of the festival, about an Australian inclusion during his visit to Australia in 2005.

The Director of Theatre at the Australia Council, John Baylis, successfully negotiated a relationship with the Kennedy Center and Windmill Performing Arts was invited to the 2006 festival. Co-founders Kim Peter Kovac and Deirdre Lavrakas continued to support an Australian entry in 2008, 2010 and 2012. The Australia Council Annual Report for 2005/2006 lists the New Vision/New Voices relationship as a major highlight for Theatre in that year.

Lowdown promoted Australian TYP (Theatre for Young People) companies during the event and reported on the experience.

Queensland youth arts funding, 2008

In 2008, Lowdown looked at the introduction of a new arts business funding model. Saffron Benner presented the outcomes and discussed the issues with affected companies.

Feel the Power of Canberra, 2008

Canberra, Australia’s capital city, is home to some of Australia’s most vibrant youth arts companies. In 2008, Estelle Muspratt gave an overview of the sector – and dispelled a few myths along the way.

The 2008 UNIMA Congress in WA

The 20th UNIMA World Congress and International Puppetry Festival was held in Perth, the first time a UNIMA Congress had been held in the Southern Hemisphere. It featured an international festival and workshops, masterclasses, forums, a One Million Puppet Project – a Guinness World Record attempt at having the most amount of puppets in one site – and a Puppet Caravan that traversed the country over four and a half weeks.

Are You Ready to be Human? ASSITEJ, 2008

Lowdown Editor Jane Gronow commissioned Caroline Reid to profile ASSITEJ, the International Association of Theatre for Children and Young People, in an interview with 2008 ASSITEJ Artistic Director Jason Cross and the President of ASSITEJ, Germany’s Wolfgang Schneider. What is it? Where did it come from? What is its relationship to its members?

Lowdown's complete 2008 ASSITEJ Congress coverage

Once again, an ASSITEJ World Congress in Adelaide would have a dramatic effect on Australian and world youth arts, and once again Lowdown was on hand to cover it. Editor Jane Gronow’s June 2008 issue featured 16 pages of reviews and commentary on ASSITEJ 2008, the 16th World Congress and Performing Arts Festival for Young People.

With a program of 33 productions, two conferences, twelve forums, three Playwright Slams and numerous other workshops, activities and events, the Congress attracted thousands of national and international artists, artsworkers and delegates, including 480 registered delegates from 47 countries.

NSW Arts Funding, 2009

In the wake of changes in Arts NSW funding arrangements for 2009, Phoebe Macrossan set out to investigate decisions affecting NSW companies, Arts NSW’s direction for young people and the arts and the general feeling of the youth arts sector in NSW.

The 39th Danish Festival for Children and Young People, 2009

In August 2009, Lowdown Editor Jane Gronow reported from the 39th Festival for Children and Young People in Ballerup, Denmark.

Presenting Lowdown Online, 2009

Jane Gronow’s editorial in the June ’09 issue indicated the new direction for Lowdown:

‘The big announcement for this issue of Lowdown is Lowdown Online – the national online information and discussion resource for youth performing arts in Australia. Lowdown will transition over the next six months to online delivery.’

The Last Lowdown, December 2009

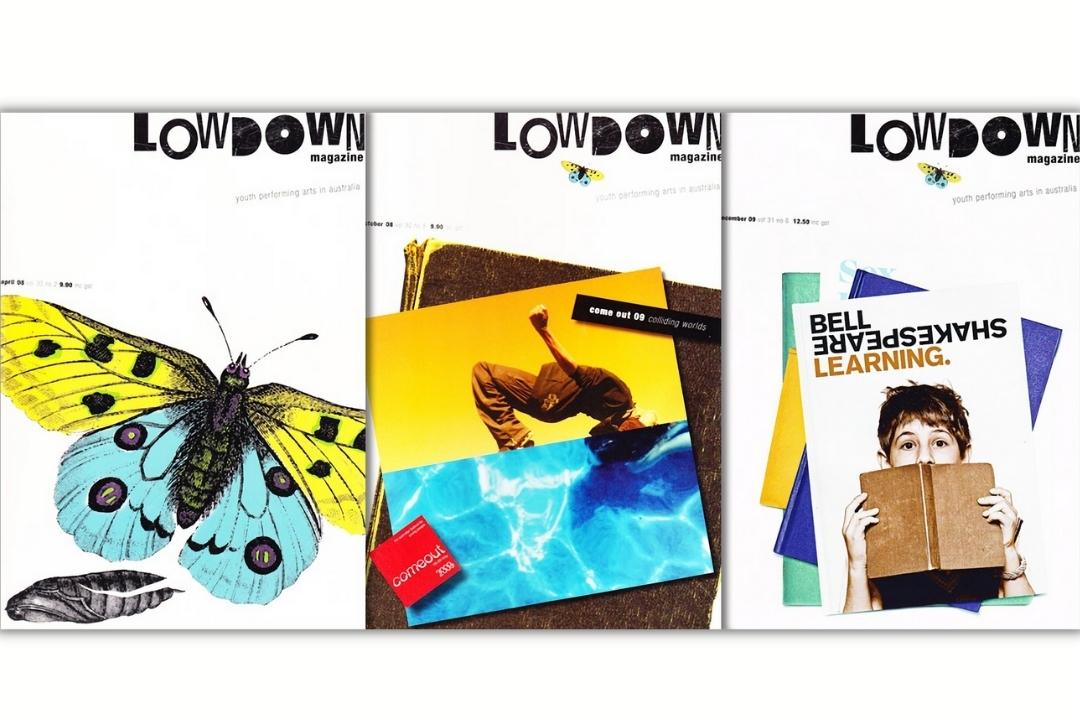

Over the final three issues of Lowdown the magazine gradually reduced in size, from 48 pages to 20 pages, as it migrated its regular columns online. Shorn of the text-heavy state and territory news columns, which were indeed more suited to an online database than print, these last three issues elegantly encapsulated Editor Jane Gronow’s approach. Each is beautifully designed, with meaning created not only by the text but by the careful selection and placement of the accompanying colour illustrations.

2000-2007 History and Commentary

Lowdown and the New Millenium

2000-2007

A history and commentary by Tony Mack

Introduction

Once again Lowdown started a decade with a new editor. In this case the new editor, Tony Mack, now precipitates a change to the point of view of this commentary and history. As I am that editor, this section of commentary will now be written in the first person, following the general Australian rule that only politicians and sports stars are allowed to refer to themselves in the third person.

The beginning of the 2000s brought to a head a number of issues that had been simmering throughout the 1990s around the participation of young people in youth arts and in the arts in general. In the broadest sense this related to an Australia-wide issue highlighted by Mark Davis’ 1997 book Gangland: Cultural Elites and the New Generationalism[1]. Davis argued that a cultural élite in Australia (such as Phillip Adams, Robert Hughes, Robert Manne, Helen Garner, Beatrice Faust, etc.) had been given prominent leadership roles in their 20s in the 1960s and 1970s and continued to dominate the public spaces of cultural debate a quarter of a century later. Rather than mentor young people into the same opportunities they themselves had been given, Davis argued that an older generation, in many public spheres of Australian life, had ‘more or less systematically set out to discredit young people and their ideas, even progressive opinion generally’.

I was sympathetic to this argument, having seen some evidence throughout the 1990s. As a teenager in the 1970s I had co-founded the Malvern Youth Theatre and been involved in 16mm filmmaking in Melbourne with AFI award winning teams. I attended the 1975 Australian Youth Drama Camp in Canberra and met (then and later) youth arts practitioners such as Derek Nicholson, Graham Scott, Errol Bray, Nigel Triffitt and Joan Pope. Moving to Sydney, I trained as an actor and worked throughout the country as an actor, playwright and director in film and theatre during the 1980s. By the early 1990s I had founded a Theatre for Young People and become a Lecturer in the Department of Drama at the University of Adelaide. Looking back to the leadership opportunities I had experienced as a young artist in the 1970s, and valuing the development those opportunities had given me, I sought to give my university students and young actors working for me access to similar experiences.

Changes to the tertiary education sector by the ‘Dawkins Revolution’[2] made this difficult. Not only were young people now paying, through HECS[3], for the free university education enjoyed by baby boomers, they also had to endure a radically inferior teacher/student ratio due to the implementation of a funding structure based on the ‘EFTSU’ (Equivalent Full-Time Student Unit) in performing arts programs. Career options for younger academics disappeared as an older generation preserved tenure and generous superannuation packages[4] for themselves at the expense of younger academics, who were expected to gain higher qualifications, write more research papers and teach more students while employed on a casual basis, often in a toxic work environment[5].

I found the diminishing leadership opportunities for the next generation of artists in the wider performing arts sector in Adelaide deeply disappointing. Theatre companies like Red Shed, Junction, Harvest, Magpie and Carouselle were being wound down. The State Theatre Company, with the return of founding Artistic Director Rodney Fisher, seemed to be slipping into genteel middle age, restaging old productions like The Department and Master Class to a greying, but dwindling, audience of loyal and nostalgic subscribers. In drama in education, as well as community arts, many of the leaders remained the same as a decade before or more, albeit with a different job title. New positions seemed to be apportioned to peers who were known, trusted and spoke the same exclusive language.

For me the situation was unacceptable, as I felt that a proportion of the students I was teaching were exceptional. The culmination of the degree course at the Department of Drama at the University of Adelaide at that time was the ‘C-Prods’. This was a year-long program for directors originally developed by the founder of the Adelaide Fringe and Cabaret Festivals, Frank Ford AM, where students would learn the basics of direction in the first semester and direct their own production in the second semester. Upon taking over this series of subjects from Frank Ford I found, much to my surprise, that students in this course were producing some of the best theatre in South Australia at that time. More than that, many of the student directors were far more confident and aesthetically successful in combining media and technology in performance than experienced professionals I had worked with. At times I felt like the student, as I encountered wildly innovative theatrical approaches to contemporary performance.

Clearly a new, more visually and aurally literate generation was experimenting with the influences they had grown up with, and because they had grown up in an exceptional period of change their work had a dynamism that made theatre of a previous generation look pedestrian. Later, after I had left the university and taken on the role of Lowdown Editor, the then-Artistic Director of Arena Theatre Rose Myers introduced me to the writing of American media theorist Douglas Rushkoff. His writing articulated some of the changes I had observed. In Children of Chaos, he takes a provocative look at how the culture of children and young people can give adults the tools for survival in the increasingly complex 21st century:

‘Children born into our electronically mediated world of computer and television monitors might best be called “screenagers.” While the members of every generation experience some degree of tension with their own children, today’s screenagers have been forced to adapt to such an extent that many of their behaviours are inscrutable to their elders. We feel threatened by how different they have become. Indeed, screenagers appear to be interacting with their world in ways that are as dramatically altered from their grandfather’s experience as the first winged creature from their earthbound forebears…

‘Today’s renaissance marks a moment when human beings have achieved the ability to direct certain aspects of their own evolution through their cultural and technological innovations. In this sense, our computers and networks aren’t doing anything to us — we are doing something to ourselves through these new tools…

‘Because they are less entrenched in and committed to business-as-usual, young people appear much more willing to accept cultural change as a natural, even pleasurable, evolutionary process. From young people’s perspective, the new sorts of games, sports, television programs, fashions, and interactive media that they have embraced over the past decade all teach them coping strategies for the chaotic, highly networked culture of which we are fast becoming a part.’[6]

The Information Revolution had now progressed to the stage that seemingly limitless possibilities and mountains of information were electronically accessible (even with most people on dialup internet and before the advent of social media later in the decade). While older generations struggled with this development, young people skated, slid, and snowboarded over, across and around these mountains of information, finding new connections along the way[7].

In this context, it is clear that if Lowdown was to continue to comment authoritatively on youth arts then the insights and accumulated knowledge of its most experienced writers would have to be supplemented with the views of Rushkoff’s ‘screenagers’. More than that, I was determined that they and other youth-focused subcultures should speak, where possible, in their own words to Lowdown’s readership, and not be mediated by older writers. This sense of balance and inter-generationalism was to be at the core of its new editorial policy, and corresponded with a number of changes taking place around the country. Little were we to know this new focus on a ‘next generation’ in Australian youth arts was to help make Adelaide, once again, the centre of world youth arts in 2008.

2000-2002: The Children of Chaos

By the end of 1999, I had edited two issues of the magazine and attended the national YPAA conference in North Melbourne, enabling me to network with people from the youth arts sector around the country. The experimentation in the work happening nationally confirmed my belief that a new generation of theatre makers needed to be profiled and supported. It also reinforced for me the central role Lowdown played in the sector. Actors, directors, designers, puppeteers, youth arts workers, funding bodies, academics, researchers, arts centres and arts organisations were using the magazine in a variety of ways – as a required text in universities, a model for review writing in schools, in research, for ideas and contacts, and for benchmarking best practice at a national level. The previous Editor, Belinda MacQueen, had not only left Lowdown in a healthy financial state, she had also effectively networked throughout the country with its many stakeholders.

The first and third editorials for 2000 set out my vision for the magazine, very much built on the strengths of the past. The first editorial quoted Rushkoff and his call to use young people as guides into the future, as Lowdown embraced the change of the Information Revolution and dared to be optimistic in its hopes for the coming decade[8]. By June, I could point out new trends, such as a host of new young writers like Kate Mulvany (WA/NSW), Lana Gishkariany (Qld), Rachel Paterson (SA), Neville Talbot (WA) and Angela Warren (Tas). Soon they would be joined by others – Anna Held (SA), Lucy Evans (NSW), Caroline Knight (ACT), Esther Lamb (SA), Lenine Bourke (Qld), Tom Holloway (Vic), Fin Kruckemeyer (SA) and Estelle Muspratt (ACT), to name a few.

In order to create a ‘must-read’ magazine for the industry, I placed a strong emphasis on variety, ‘with hard-edged policy discussions followed by “colour” articles that give a real sense of the performing arts experience, followed in turn by profiles of companies or projects’[9]. The policy articles sought to encourage youth artsworkers to engage actively in sector-wide debates and were sometimes quite challenging, such as Judith Mclean’s ‘Strategic Alliances for Aesthetic Product’[10], where arts workers were compared to travel guides for an aesthetic experience. Lowdown closely followed the Australia Council’s recently developed Youth and the Arts Framework and its Youth Arts Panel, which had an organisation-wide brief to bring about changes to make the Australia Council more child and youth friendly. The Major Performing Arts Inquiry (known as the Nugent Inquiry after its Chair, Helen Nugent) was also followed and its implications for youth arts dissected, and discussions on sponsorship and marketing were initiated.

The focus issues that MacQueen initiated continued, and I began to spend months on background research on the areas covered in these issues, locating key companies and players nationwide and current issues affecting their work. In the June 2000 issue the magazine focused on the historical ‘Living Journeys’ of longstanding youth arts companies in every State and Territory of Australia for Lowdown’s 21st birthday issue[11]. This was also the first issue that tried to explore the history of YPAA and Lowdown, with pieces by YPAA veterans such as Joan Pope, and Michael FitzGerald, as well as former editors Geoffrey Brown and Rachel Healy.

The next issue looked at what youth arts was providing for a multicultural Australia, and the opportunities for artists from non-English-speaking backgrounds[12]. A focus on young emerging artists in December 2000 was written, for the most part, by young emerging artists – providing some with their first-ever payment for their creative work[13]. In 2001, focus issues included new technologies in live performance[14], regional youth arts companies[15] and performing arts experiences for those with a disability or deafness[16].

I was particularly proud of the youth dance focus in the April 2002 issue (which also included an exclusive interview with the filmmaker Phillip Noyce about directing Indigenous children in his film Rabbit Proof Fence). Looking at definitions of youth dance and best practice, it profiled a number of key practitioners and companies. Gerard Veltre interviewed Peter Stock about the annual dance festival Stamping Ground in Bellingen, NSW. In Tasmania, Stompin’ Youth’s new Co-Artistic Directors, Luke George and Bec Reid, talked about the future of the company, and there were other profiles of Mark Gordon and the Choreographic Centre (ACT), Ruth Osborne and Quantum Leap Youth Choreographic Ensemble (ACT), Felicity Bott and STEPS (WA), South African choreographer Sbonakaliso Ndaba and Kylie Ball at Extensions Youth Dance Company (Qld)[17].

Lowdown’s international coverage continued with a focus on Asia and the Pacific, apart from sporadic articles from Lisa Cameron in Germany. Youth arts in New Zealand, Fiji, Vanuatu and even the tiny island nation of Kiribati were profiled. Lana Gishkariany’s article on the exchange between Kite Theatre in Brisbane and the Te Itibwerere Community Theatre from Kiribati was the first of a number of Lowdown profiles of youth arts in some of the remotest corners of the globe.

Due to the change of staffing at Youth Performing Arts Australia (YPAA) and in ASSITEJ representation, it took some time to begin to consistently relay ASSITEJ news through the pages of the magazine. Nicole Beyer had replaced Michael FitzGerald as the Executive Officer of YPAA in Melbourne, and although regularly assisting the Australia Council with a host of requests regarding youth arts and its processes, her position remained half-time and unsupported at a federal level. She initiated a Regional Youth Performing Arts Initiative in 2000 (which did get federal support) with projects involving young people in Tasmania, NT, Victoria, Queensland, SA, WA and NSW and began work on a 2001 National YPAA Conference before leaving YPAA in December 2001.

The YPAA Board then closed its office in Melbourne and moved YPAA back to Carclew, employing a new SA-based Executive Officer, Natasha Phillips, originally from Adelaide but at that time more well-known as the Director of the Courthouse Youth Arts Centre in Geelong. Building on Beyer’s extensive groundwork, Phillips developed the 2001 Critical Conference into an influential national forum and showcase at the Sydney Opera House in October 2001, with keynotes from renowned US theatre director Peter Sellars, the Opera House CEO Michael Lynch, Windmill Performing Arts’ Cate Fowler and the Indigenous youth arts practitioners Karl and Waiata Telfer, who were the Associate Directors of the Adelaide Festival for the Arts. The hard work and high visibility of YPAA in Sydney, the home of the Australia Council, paid off. YPAA’s next federal application for funding was successful and it was once again able to resume activities full-time in 2002.

With the next ASSITEJ World Congress to take place in Seoul, Korea in July 2002, Lowdown published an overview of the International Association of Theatre for Children and Young People from ASSITEJ representative Lou Westbury in February 2002[18]. In it she reflected on her term, from the last Congress in Tromso, Norway, to meetings in Dallas (USA), Harare (Zimbabwe), Tokyo (Japan) and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil).

As Australia’s Congress contingent were packing their bags, there were a host of changes that occurred that affected YPAA, Lowdown and Australian youth arts. The most seemingly mundane of them was one of the most influential – Carclew had a new website. At that time the South Australian Government was upgrading its websites and I was given project management of the new Carclew website development, along with a hefty budget. For the first time Carclew had a dynamic presence, and staff could upload and update information about their projects. (This was less commonplace in 2002, with most workplaces still on dialup internet and even large media organisations having the most basic static, unchanging, websites.) There were forums and the precursors of blogs, and news functions of Lowdown could be accessed online, with daily updates. Each page was loaded with metadata so that Carclew projects would regularly feature first in global searches of any aspect of youth arts, causing traffic to increase by more than 400% in the first few months and over 1000% in a year. The international traffic was very strong, and Carclew’s online visibility as a world leader in youth arts was to prove very handy in the coming years.

Changes in staffing were felt keenly. The redoubtable Leigh Mangin, whose multiple skills had helped keep Lowdown afloat for almost ten years, moved upwards within Carclew Youth Arts to more senior management duties at the Odeon Theatre in Norwood. The nearest thing to an irreplaceable staff member, she was replaced by Melissa Tilbrook in marketing, but continued to design the magazine and assist the Editor for some time to come. Her passionate belief in the important role of Lowdown in youth arts, as evidenced by her August 1996 editorial as acting Editor, was communicated to stakeholders around the country in her daily dealings, and her cheery professionalism was valued by all.

At YPAA, Natasha Phillips resigned and Christine Schloithe acted as Executive Officer until the new EO, Anya Maclay, came on board. After a surprise nomination by NSW YPAA members, I had been elected as the new ASSITEJ representative by the YPAA Board, to follow on from Lou Westbury and Michael FitzGerald. As I was not the most experienced traveller, nor a great authority on ASSITEJ, I was looking to the Congress in Korea with some trepidation, but knew that for Lowdown the possibilities for international coverage were exponential. New South Wales members had charged me with extending the national advocacy I was doing at that time for Australian companies into an international arena, and I had bemused Theatre staff at the Australia Council with an ambitious proposal to use the ASSITEJ network to develop Australian Theatre for Young People (TYP). In a series of meetings I proposed specific targets from 2002-2005 for international tours, professional development, publications, international forums, cultural exchanges and the promotion of Australian TYP. I’m not sure whether they believed me – I didn’t know at the time whether I believed myself and would have been dumbfounded to discover I would exceed all targets – but they did invest $13,000 for airfares over the next three years.

On my way to Korea, I stopped off at Singapore airport to await my flight to Seoul. By chance I bumped into Frank Ford, who had employed me at the University of Adelaide, while on his way back from an opera festival in France. Having set me on a most interesting journey in the 1990s as a university lecturer, it somehow seemed fitting that he should feature at the beginning of an exciting new journey in the 2000s.

2002-2005: Lowdown International

It wasn’t until I witnessed an incident at a folk village excursion in Seoul, Korea during the 2002 ASSITEJ World Congress that I fully understood the impact of Lowdown on world youth arts. I had distributed copies of the latest issue to all official delegates from about 45 countries, and soon a circle of theatre practitioners and festival directors from Russia, Korea, the USA and Denmark were flicking through it while discussing the work of Arena Theatre in Melbourne. It became clear that much of the detailed knowledge of influential decision makers about Australian youth arts companies came from Lowdown’s articles and reviews.

This was only one of number of surprises throughout the Congress. The Australian delegation included Lou Westbury, Michael FitzGerald (who had come to accept his lifelong award of the title ‘Honorary President’), Judy Potter (Carclew Director and YPAA Chair), Sally Chance, Jane Neville, Jennifer Nicholls, Cate Fowler and a contingent from Buzz Dance Theatre, who were performing in the official program. The Australian delegates assisted in promoting a bid for an Adelaide Congress in 2005, but were soundly beaten by the favourite, Montreal, and I resolved to leave any further thoughts of another Australian Congress to a distant future.

As Margaret Leask and her delegation from AYPAA had done all those years ago in 1975, I took my place as a national representative at Australia’s table amongst all the other countries at the triennial General Assembly of ASSITEJ. I was thrown into ASSITEJ politics almost immediately, being nominated to a panel to rewrite the Working Plan for ASSITEJ activities for the next three years. As an editor, this was a fairly straightforward task in terms of framing language, especially after tensions were settled amongst some of the panel members who suspected undermining of the soon-to-be President, Wolfgang Schneider, who had written the original document rejected by the Assembly. The revised Working Plan sailed through the next day without a hitch, and when elections for the next Executive Committee occurred a day later I ended the day as an ASSITEJ Vice-President after being nominated by the Secretary General, Sweden’s Niclas Malmcrona, much to my astonishment.

Apart from the Congress and Festival, Lowdown was able to catch up with Australia’s Roger Rynd and his new Korean venture LATT Children’s Theatre, which was privately funded by the Korean billionaire Park Myung Shin and his English language company Unibooks[19]. My enthusiasm for what I later felt to be one of the most successful ASSITEJ Congresses was not quite shared by Jennifer Nicholls in her Lowdown coverage of the Congress[20]. While generally positive about the first Asian Congress, including great productions such as the Danish Small Touring Theatre Company’s Hamlet and Performance Group Tuida’s The Tale of Haruk and PMC’s Cookin’ from Korea, Nicholls noted a series of ‘divides’. The average age of ASSITEJ delegates appeared about 55 while performers averaged 25 years old, and an ‘ageing European’ contingent still seemed in control of ASSITEJ activities. She was critical of the Australian production, The Cave, and blistering about the ‘spectacularly awful’ Chinese production of The Happy Bird. (The message for children from this elaborately staged work from Hangzhou Yue Opera Troupe appeared to be, ‘Work hard or die horribly’.)

Back in Australia, the year ended with one of my favourite issues of Lowdown. I had worked with Waiata Telfer, the Kaurna/Narrungu arts practitioner, to co-edit a theme with an Indigenous focus and largely written by Indigenous writers. Jared Thomas wrote about Indigenous cultural content in art, there were profiles of Yirra Yaakin in Perth, the Port Youth Theatre Workshop[21] in Adelaide, Kooemba Jdarra in Brisbane, PACT Theatre’s Stand Your Ground project in Sydney and a Third Place project from Contact Inc. in Brisbane[22]. The front cover, featuring young women from Port Youth Theatre Workshop and designed by Leigh Mangin, was a playful homage to the classic Brady Bunch opening and closing sequence of members of the family looking at each other from separate boxes (in the colours of the Aboriginal flag of course.)

Although I contributed, in that issue, an article on international developments in Germany and the birth of the Epicentre network in Croatia based on a trip to Europe I had made in late 2002[23], the new TYP review and Lowdown coverage of the debate surrounding that was of far greater interest for Australian readers.

The last Australia Council document on Theatre for Young People (TYP), a major subsector of theatre performing at that time to over two million people a year[24], was written in 1991. It was part of a policy document effectively banishing Theatre in Education, as an artform, from Australia Council funding[25]. On the record in this document were a number of disparaging remarks about the standard of TYP in Australia. Yet with neither a 1992 national meeting of TYP Artistic Directors nor the Australia Council able to articulate a vision of how TYP was different from other theatre, its special relationship with its audiences or what kind of standards TYP should aspire to, the matter was allowed to lapse with no constructive strategic developments.

Throughout the 1990s, iconic Victorian and SA TYP companies were defunded[26] and at the beginning of the 2000s it was the turn of NSW companies. In Sydney, REM Theatre lost triennial funding in 2001, Theatre of Image lost their triennial funding in 2002 and Freewheels in Newcastle had both state and federal funding slashed. A paper presented to the Theatre Board pointed out that Theatre for Young People funding was $600,000 less in 1999/2000 than a decade before, and it had reached a point where there was almost no federal funding for professional theatre for children for the Greater Sydney area, where up to 30% of Australia’s children resided.

The NSW Ministry for the Arts had requested an Australia Council review into TYP which John Baylis, the Manager of the Theatre Board, had initiated. Lowdown published Baylis’ introduction to the Review, then its own three-page article by Jane Woollard detailing concerns of NSW companies and the shortcomings of TYP investment in Sydney in particular[27]. A heated, and ultimately productive, phone call ensued between the normally genial Baylis and myself when the draft Lowdown article was sent to the Australia Council for comment. At the crux of the matter was his belief that the Theatre Board be impartial, with no preconceived opinions, and respond to applications against the published criteria[28]. With these assumptions it was therefore unfair to criticise the Board for uneven coverage of arts funding across all regions. The crux of my argument was that if a process of peer review allowed 30% of the country’s children to have less access to the arts than most of the rest of the country then there was something wrong with that process. Rather than merely reacting to developments, I felt that it was time for the Australia Council to be more proactive in initiating change so that more opportunities were created for people to participate in the cultural life of the country.

My editorial in the next issue categorised the reducing level of arts funding for children and young people from the Theatre Board and some State funding bodies as a ‘line in the sand’ issue[29] – ‘I cannot find any philosophical justification for not investing in the arts at the same levels for children as for adults’.

The publication, in the same issue, of a paper for the Theatre Board by Queensland’s Judith McLean and Susan Richer designed to provoke and prompt discussion, ‘Theatre for Young People in Australia’[30], divided opinion nationally. While there was strong support for some of the provocations, about the relationship between artmakers and young arts participants, the future of technology in performance practice and fairness in public spending, there was disquiet amongst some practitioners at other sweeping statements.

Most Australian companies (excluding Arena Theatre Company and Zeal Theatre) were presumed incapable of matching ‘the quality and innovation demonstrated by Denmark and Norway’s companies’. Practitioners were accused of a lack of intellectual rigour, and were reminded that ‘exposure in the arts does not equate with understanding’. McLean and Richer appeared to propose that artists with an awareness of the philosophical intent of their work should take priority in public support for the arts. Some theatre artists, wary of the power of academics and critics in the arts in other countries and artforms, worried that the latter point signified a shift in emphasis from practice to theory, and the privileging of an exclusive language to describe art and artistic intent.

The ‘Review of Theatre for Young People in Australia’ was completed by Brisbane-based consultancy Positive Solutions in December 2003. Its recommendations were clustered in three areas – developing the audience and the market, enhancing the strength of the sector and forging partnerships with education[31]. A number of strong results would be achieved in the area of developing the audience and the market, but its idea of a national TYP centre similar to Germany’s Kinder- und Jugendtheaterzentrum in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (universally known by its acronym KJTZ) would be rejected. Once again, the national funding body seemed wary of national projects.

The health of small to medium-sized theatre companies was also analysed by another report released by the Australia Council in December 2003[32]. This confirmed the stress being felt within many youth arts companies that Lowdown had been reporting throughout 2003. One such article was from the outgoing Artistic Director of Riverland Youth Theatre, Fraser Corfield, titled ‘The ADs, They Are a Changin’[33]. In it he noted that half the artistic directors (the ‘ADs’ of the title) of youth theatres receiving funding from the Australia Council were resigning within a three-month period. As he pointed out, such a wholesale exodus of talent and corporate knowledge would (and should) be considered a major concern in any industry in Australia.

The Ian Roberts analysis for the Australia Council detailed why. Dubbed as the ‘powerhouse of the artform’, youth arts companies comprised a large part of the small to medium-sized companies analysed. While producing far more new Australian plays and international tours than major performing arts companies at a fraction of the cost, these companies were found to be under resourced and financially at risk, and their staff poorly paid and overworked. It was now apparent that there was a real crisis in Australian theatre that would have to be addressed in the coming years.

Throughout 2003 and 2004, Lowdown continued to reach out to new audiences with its focus issues – such as on arts training and education[34], youth arts within major cultural institutions[35], music programs[36] and arts for young people with disabilities[37]. I was able, at no cost to the magazine, to contribute in these years substantial international coverage. Youth arts festivals in Wales and Denmark were covered during the outbreak of the Iraq War and SARS epidemic[38] and I launched a book I had co-edited, ‘The ASSITEJ Yearbook 2002/2003’, in Austria in late 2003 at the Theaterhaus für junges Publikum in Vienna[39]. Hosting a symposium in Tokyo in July 2004 enabled me to cover the International Children’s Theatre Festival there[40], and a 2004 ASSITEJ Executive Committee meeting in Amman, Jordan at the height of the war in neighbouring Iraq gave me access to Middle Eastern youth arts activities that I profiled for Lowdown’s readership in ‘ASSITEJ in Jordan’[41].

At YPAA, Anya Maclay had initiated a collaboration with Youth Arts Queensland to ‘piggyback’ a national conference on the Queensland event On the Axis in late 2003. In mid-2003, after she left the position, YPAA ended up with both a new Chair, Suzanne Davidson and Executive Officer, Deidre Williams in a short period of time and both attended the event. (And around that time there was also a new Director of Carclew, Jessica Machin.) On the Axis was a successful national gathering of youth arts practitioners in Townsville, and Queensland backed it up with an Out of the Box Symposium at the Queensland Performing Arts Centre in Brisbane shortly after, creating a valuable forum for philosophical discourse about youth arts practice. With new energy from Queensland and a strong leadership core in Sydney, national networking was beginning to improve and YPAA continued its important role in a national youth arts dialogue.

On 24 April 2004 Youth Performing Arts Australia changed its name to Young People and the Performing Arts. While the acronym, YPAA, remained the same, Deirdre Williams and the YPAA Board envisaged a far greater brief for the small organisation. Not only youth performing arts, but all youth arts would be represented. In order for this not to end up as a Herculean task, Williams would recast YPAA as ‘a small but effective lobbying and advocacy body’[42] akin to the Arts Industry Council of South Australia or the National Association for the Visual Arts. Training the YPAA membership to assist with that advocacy further relieved the YPAA head office’s limited resources. At the launch of the name change, YPAA announced the development of an Arts Advocates Tool Kit – launched in October 2004 – as well as an annual professional development event.

YPAA’s next collaboration was with SA’s Come Out Festival and ASSITEJ in early 2005. As ASSITEJ Vice-President, I had invited its Executive Committee to have a meeting during Come Out 2005. The aim was ‘to showcase Australian work to the world’, and the Australia Council’s Audience and Marketing Division was persuaded to ‘value add’ to this by supporting a series of pitches by Australian companies to key international presenters. YPAA also hosted an international TYP Symposium on theatre making for young audiences[43].

Hosting some of the world’s influential youth arts practitioners from over fifteen countries, along with a sizeable Japanese contingent, provided some valuable lessons (and some great coverage for Lowdown). Much of the Australian work – such as the extraordinary Christine Johnston (Qld) as Madame Lark, Patch Theatre’s Emily Loves to Bounce (SA) and Real TV’s Children of the Black Skirt (Qld) – was of a high standard, and the kind of quality that would grace any international festival. Other work, however, was not, and the creative development processes of Australian TYP companies sometimes seemed to fail in the narrative basics of theatre – taking the audience on a journey. The endless diet of speeches at every event by South Australians became a source of amusement to national and international guests, and there were other deficiencies in cultural sensitivities by us as hosts. And when it came to pitching their work to international presenters some Australian companies were, quite frankly, hopeless.

The experiences during this time corresponded with my experiences in soliciting invitations for Australian TYP companies to international festivals. By 2005, these invitations were now beginning to come more often, especially from Asia and North America, the areas I had targeted as having most potential for growth. Yet too often an unevenness in professional standards would arise – while the artistic product may be wonderful, a company’s communication and negotiation skills may be negligible. Sometimes companies simply froze at the opportunities that now began to appear for them[44].

If YPAA was to lobby and advocate for youth arts, and I was to continue to promote it internationally, it was essential that the Australian ‘brand’ delivered high standards in all areas. I felt professional development had to be a focus area, for Lowdown and Australian youth arts.

Soon this was evidenced in the pages of the magazine and in collaborations with the Market Development section of the Australia Council. An ASSITEJ colleague, Kim Peter Kovac, was the Producing Director, Theatre for Young Audiences at the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC. In the June issue immediately following the Adelaide meeting he wrote an article with advice on how to pitch to presenters, ‘Zen and the Art of Selling Shows’[45]. Not only was this useful for Australian companies, it was later used as a paper at a Mid-Atlantic Arts Conference and distributed in the US.

Kovac invited me to the US at that time to deliver the keynote address at the Bonderman Festival of Playwriting for Youth in Indianoplis, Indiana. In ‘The Bonderman’[46], I reflected on both the challenges and the achievements of Theatre for Young Audiences (TYA) in the USA. While the American shows were conservative in both form and content by Australian standards – they responded to box office constraints whereas Australians responded to a call for ‘innovation’ from funding bodies – it was clear that their sector had a strong culture of professional development and regard for the craft of the playwright. I felt we could learn from some of the discussions they were having, and also begin to network more strongly with the largest English-speaking market in the world.

The other ‘gathering of the clan’ for American TYA practitioners was New Visions / New Voices, also a festival of play development, at the iconic Kennedy Center[47]. Kim Peter Kovac and Deirdre Kelly Lavrakas had co-founded this in 1991, and it had had helped to develop some of the finest American TYA plays of that time, such as Wrestling Season and Selkie (Laurie Brooks), Dragonwings (Laurence Yep), The Yellow Boat (David Saar), Afternoon of the Elves (Y York) and In the Suicide Mountains (James Still). Kovac and I had approached the Australia Council with the idea of Australia having a presence in this formerly US only event in 2006. After months of consideration and negotiations between Kovac and the Theatre Board’s John Baylis, the answer came back as a yes.

It was at this time another professional development and showcase opportunity presented itself, an opportunity of a scale that Australia hadn’t seen for twenty years. In mid-2005, Carclew Youth Arts decided to submit a bid for another ASSITEJ Congress in Adelaide in 2008.

2005-2007: Towards another Congress

The decision to bid for the Congress came as a direct result of discussions held during the Adelaide Executive Committee meeting between Executive Committee members and the Director of Carclew, Jessica Machin. Sally Chance (the Director of Come Out Festival), Deirdre Williams (Executive Director of YPAA) and I had had serious reservations about such a bid. A 2008 Congress would fall in a non-Come Out year (Come Out being a biennial festival), so a whole new festival would have to be created. YPAA had just initiated a new lobbying and advocacy focus, and wanted to steer clear of initiating major projects and events. I wanted to continue to spend the next three years developing an international infrastructure for Australian TYP – such as international tours and professional development opportunities like New Visions / New Voices in the USA, the International Directors Seminar in Germany and connecting Australian companies to an Asian festival touring circuit. And on top of that, with less than three years to prepare, it was an impossibly short timeframe. In earlier talks in 2004 with Machin, we had all strongly advocated for a 2011 rather than 2008 bid.

For ASSITEJ however, the lack of bids for a 2008 Congress had been worrying and ASSITEJ officials were on a charm offensive. Only one bid was likely to be received, from Wales in the UK. The ASSITEJ President, Wolfgang Schneider, and others openly courted bids from other countries, which would give the ASSITEJ world membership more leverage in negotiations between bidders. In Adelaide the idea quickly took hold, and within a short time had developed a momentum of its own.

John Hill, the Minister Assisting the Premier in the Arts[48], was enthusiastic, as was the South Australian Youth Arts Board. The Australia Council had just instituted a focus on TYP from 2005-2008, a timeline which seemed to tie in perfectly with a 2008 Congress. More than that, the event promised two major outcomes – great performance experiences for tens of thousands of South Australian children and young people and incredible networking, showcasing and job opportunities for hundreds of Australian theatre artists and dozens of companies. With so many diverse interests aligning at the one time, it was an unmissable chance to launch the generation of Australian theatremakers I so admired on to a world stage.

The two-person bid team started work. The Executive Producer of the Adelaide bid, Carclew Director Jessica Machin, lobbied for state and federal funding commitments and major corporate partnerships, and produced a comprehensive and beautifully presented bid document. Meanwhile I focused on the intricate mechanics of getting the votes from ASSITEJ countries around the world, and turning around the minimal chances Adelaide had against a European-based Congress in the UK[49]. The rest of 2005 went by in a blur with the both of us in constant motion.

Lowdown, however, didn’t suffer as a result of this. Leigh Mangin returned, once again, to act as Co-Editor for the August 2005 issue and the October issue was another stunning issue focusing on Indigenous youth arts, co-edited by Lee-Ann Buckskin[50]. The issue featured the Garma Indigenous Cultural Festival (NT), Wesley Enoch with Ilbijerri and Polyglot Theatre’s Headhunter (Vic), Lee-Ann Buckskin’s Indigenous Arts and Culture Program at Carclew (SA), the Australian Aboriginal Theatre Initiative in New York and Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre (WA).

An outpouring of energy from the ACT was also reflected in the pages of Lowdown at this time. Jigsaw Theatre’s gritty new production Vin, about young men and their sexuality, was featured in June 2005 along with an extraordinary youth dance project at the Australian War Memorial, Quantum Leap’s Reckless Valour[51]. Soon to follow were profiles on Hidden Corners, a youth theatre company for young carers[52], the Fourth International Museum Theatre Alliance in Canberra[53], Canberra Youth Theatre’s public art event Arcane Secrets[54] and another Quantum leap youth dance project at the National Gallery of Australia[55].

In late October a bid team including the SA Minister John Hill travelled to Montreal in Canada to present Australia’s bid for the 2008 Congress. While very successful for Australia – Lowdown’s October issue broke the news that we had won the Congress and Zeal Theatre had won the prestigious ASSITEJ Honorary Presidents Award – the Montreal Congress was a curious affair. From the start the Québécois theatre artists showed a puzzling indifference to national and international visitors, and a generously high regard for their own work. Networking was difficult, as venues and accommodation were dotted across the city, and the Congress hub was opposite a park frequented by drug users, alcoholics and homeless people sleeping in the bitter cold. I was reminded that the Congress was more than a festival, it was a gathering of an international ‘family’, and an environment had to be constructed in 2008 to facilitate human interaction and connection.

After an impressive presentation that included a Kaurna[56] smoking ceremony by Karl Telfer, Adelaide won the overwhelming endorsement of the ASSITEJ General Assembly. The bid team was ecstatic, and the frenetic work over five months had paid off. Minister Hill remarked in 2013, upon his resignation from the Cabinet of the South Australian Government, that one of the highlights of his ministerial career ‘was when Adelaide won the right to hold ASSITEJ, the 16th world congress and performing arts festival for young people in 2008’[57].

Now the practicalities of developing and budgeting a world youth arts event came to the fore. In the original structure outlined to the General Assembly (similar to the 1987 model), the performing arts festival would be programmed by the Come Out Director. I would leave Lowdown in 2006 to take on Michael FitzGerald’s 1987 ASSITEJ Director role overseeing the myriad international relations and General Assembly, as the ASSITEJ Vice-President charged with the responsibility of delivering a successful Congress. Immediately after leaving Montreal, the Executive Producer changed this ASSITEJ Director role to a largely voluntary position – a Michael FitzGerald figure was deemed surplus to requirements at this Congress. As Sally Chance had announced her decision to finish her term as Come Out Director in 2007, a six-month hunt was on for a Come Out Director to program the festival of the Congress, and YPAA had just changed Executive Directors once again, from Deirdre Williams to Charles Bracewell, after a lengthy hiatus with no one in the position. With only two and a half years to deliver the Congress, Adelaide was off to a rocky and confused start.

Even with my heavy voluntary workload of ASSITEJ and Congress duties, as well as more voluntary market development work with the Australia Council, I felt that 2006 was a bumper year for Lowdown. Its network was now such that it could commission articles from anywhere in the world. Anna Held came on board as Assistant Editor, bringing a sharp intelligence and strong knowledge of contemporary theatre practice. The magazine changed its look again at the beginning of the year, with designer Bridget Briscoe eschewing its traditional gloss paper for a matt finish and a slightly grittier look. Carclew’s website also had a new, more contemporary look, but unfortunately it wasn’t just cosmetic – the whole back end of the website was replaced, and it took some time to regain Lowdown’s online visibility and previous functionality. Professional development was a focus throughout 2006, as we profiled the new national SPARK mentorships, the Indigenous Education and Training at NT’s Garma Festival, the 2nd National Puppetry Summit in Hobart, New Visions / New Voices in Washington and commissioned a checklist for independent theatre artists on how to develop a production from scratch[58]. The August issue was dedicated to innovative arts training, as we continued to hammer out a message of continual professional development to practitioners.

The magazine gave great prominence in mid-2006 to the Australia Council discussion paper ‘Make it New?’, prepared by John Baylis for the Theatre Board[59]. An amalgam of proposals and questions, it threw into question the role of the Theatre Board, triennial funding, producers and the focus on new work and innovation. Baylis proposed a Theatre Board that acted more strategically and was not afraid to intervene to create opportunities rather than merely respond to them. It also proposed a move towards creating international collaborations and partnerships, as opposed to simply funding touring.

I continued to promote Australian Theatre for Young People, the Congress and Lowdown at Performing Arts Markets in Adelaide, Tokyo and Singapore, as well as representing the Australia Council at the 2006 New Visions / New Voices in Washington. The new Come Out Director (and Festival Director for the Congress), Jason Cross, was finally appointed and I took him on a tour of introduction to international gatherings in Tokyo, Seoul and Okinawa, and later Buenos Aires.

By the end of 2006 it was clear, however, that I would not be able to continue the frenetic pace of the last four years. With some serious health scares throughout 2006, I knew that something had to give. In order to deliver on the promises made in Montreal, I decided to leave Lowdown in April 2007 to concentrate on the Congress, subsidising my voluntary work there by freelancing as an actor in films and commercials. My last editorial looked back once again at the history of Lowdown and a youth arts sector ‘with a philosophical tradition, that constantly responds to changes in youth culture and is informed by our growing knowledge of the development of children’[60].

The farewell party with my Carclew colleagues was an emotional affair, as reality hit home to me. It isn’t easy to leave a treasured job at one of the world’s finest youth arts organisations.

References

[1] Mark Davis, Gangland: Cultural Elites and the New Generationalism. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1997.

[2] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/consol_act/hefa1988221/. ‘HIGHER EDUCATION FUNDING ACT 1988’. Austlii.edu.au. 2005. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

[3] Higher Education Contributions Scheme.

[4] The Report of the South Australian Commission of Audit, entitled “Charting the Way Forward”, was completed in April 1994. The unfunded superannuation liability of the South Australian Government was one of the issues covered in that Report. The Report indicated that as at 30 June 1993 the South Australian Government’s unfunded superannuation liability was estimated to be $4.406 billion. Furthermore, the Commission found that this liability was projected to more than double in real terms by the year 2021 should no reform action be taken by the Government. A new scheme with drastically reduced benefits for new members came into effect after 31 December 1993. Members of the old scheme continued (and continue) to receive more generous superannuation benefits than their younger colleagues.

[5] Margaret Thornton (2004) ‘Corrosive Leadership (Or Bullying by Another Name): A Corollary of the Corporatised Academy?’, Australian Journal of Labour Law, Vol.17(2).

[6] http://www.rushkoff.com/playing-the-future/. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

[7] I observed an example of this action in a discussion on video games. A father, who had played Donkey Kong in the arcades of the 1980s, attempted to play the groundbreaking 1999 game Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater with his twelve-year-old son. Used to platform games and completing a game level by level, he was bewildered by the open gameplay of Pro Skater, where gamers could explore each location, do grabs, flip tricks or grinds, progress through a career or goof around with cheats, new characters and unlockables. ‘What am I supposed to be doing?’ he asked his son in frustration.

The reply was simple. ‘Anything you like.’

[8] Tony Mack, ‘Editorial’. Lowdown V.22.1, p2. Adelaide: Carclew, 2000.

[9]Tony Mack, ‘Lowdown in the 21st Century’. Lowdown V.22.3, p6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2000.

[10] Judith Mclean, ‘Strategic Alliances for Aesthetic Product’. Lowdown V.21.6, p10-11. Adelaide: Carclew, 1999.

[11] Lowdown V.22.3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2000.

[12] Lowdown V.22.4. Adelaide: Carclew, 2000.

[13] Lowdown V.22.6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2000.

[14] Lowdown V.23.6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2001.

[15] Lowdown V.23.3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2001.

[16] Lowdown V.23.4. Adelaide: Carclew, 2001.

[17] Lowdown V.24.2. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002. Unfortunately, the artwork for the front cover of the issue (at that time sold as advertising) was from another era and undercut the contemporary focus.

[18] Lou Westbury, ‘ASSITEJ: A Global Alliance’. Lowdown V.24.2, p4-7. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[19] Jennifer Nicholls, ‘Investing in Culture’. Lowdown V.24.5, p7. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[20] Jennifer Nicholls, ‘Across the Great Divide’. Lowdown V.24.5, p4-6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[21] Soon to be known as Kurruru.

[22] Lowdown V.24.6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[23] Tony Mack, ‘A River That Unites and Divides’. Lowdown V.24.6, p20-21 . Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[24] Companies and artists without state or federal funding like Brainstorm Productions, or many of the performances in the Queensland Arts Council Touring Program, are included in this figure. At this time federal funding was supporting a minority of the performances taking place for children and young people.

[25] See the commentary on this during the chapter on the 1990s.

[26] Victorian companies included Wooly Jumpers and Barnstorn. (Chris Thompson, ‘What’s the Go and What’s Gone’. Lowdown V.17.5, p19-21. Adelaide: Carclew, 1995.) SA companies included Magpie and Carouselle Puppet Theatre.

[27] Jane Woollard, ‘Reviewing Theatre for Young People’. Lowdown V.24.6, p4-6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[28] Jane Woollard, ‘Reviewing Theatre for Young People’. Lowdown V.24.6, p5. Adelaide: Carclew, 2002.

[29] Tony Mack, ‘Editorial’. Lowdown V.25.1, p2. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[30] Judith McLean and Susan Richer, ‘Theatre for Young People in Australia’. Lowdown V.25.1, p4-6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[31] Positive Solutions, ‘Review of Theatre for Young People in Australia’, p70-73. Sydney, Australia Council for the Arts and NSW Ministry for the Arts, 2003.

[32] Ian Roberts, ‘An Analysis of the Triennially -funded Organisations of the Theatre Board’. Sydney, Australia Council, 2003.

[33] Fraser Corfield, ‘The Ads, They Are a Changin’. . Lowdown V.25.1, p12-13. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[34] Lowdown V.25.4. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[35] Lowdown V.25.2. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[36] Lowdown V.26.4. Adelaide: Carclew, 2004.

[37] Lowdown V.26.6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2004.

[38] Tony Mack, ‘Shadow of War’, Lowdown V.25.3, p9-11. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[39] Tony Mack, ‘It All Comes at Once!’, Lowdown V.25.6, 2-4. Adelaide: Carclew, 2003.

[40] Tony Mack, ‘Tokyo’s International Children’s Theatre Festival’, Lowdown V.26.5. Adelaide: Carclew, 2004.

[41] Tony Mack, ‘ASSITEJ in Jordan’, Lowdown V.26.3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2004.

[42] Elena Vereker, ‘Launching the New YPAA’, Lowdown V.26.3, p3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2004.

[43] See editorial and YPAA column, Lowdown V.27.2. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[44] At one stage, I negotiated an invitation for a tour to Japan for a show from one major Australian performing arts organisation. It was to perform for a season at a 1,200 seat theatre opposite the Imperial Palaces in the heart of Tokyo. The Australian company wouldn’t return my calls or respond to emails.

[45] Kim Peter Kovac, ‘Zen and the Art of Selling Shows’, Lowdown V.27.3, p6-9. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[46] Tony Mack, ‘The Bonderman’, Lowdown V.27.3, p14-15. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[47] The Kennedy Center is the national arts centre in the USA, located just over the Potomac River from the Pentagon.

[48] Traditionally the South Australian Premier is Minister for the Arts, reflecting the regard for the arts in the State. However, most of the work in the portfolio tends to done by the Minister Assisting the Premier in the Arts.

[49] It was widely assumed outside Australia in mid-2005 that the Adelaide bid was a ‘dummy bid’, with those encouraging it having no intention to vote for it. Its function was to encourage the UK bid to be more amenable in negotiations with ASSITEJ stakeholders.

[50] Lowdown V.27.5. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[51] Lowdown V.27.3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[52] Lowdown V.27.4. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[53] Lowdown V.27.6. Adelaide: Carclew, 2005.

[54] Lowdown V.28.2. Adelaide: Carclew, 2006.

[55] Lowdown V.28.3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2006.

[56] The Congress was to be held on Kaurna land, on the Adelaide plains.

[57] John Hill, email to Director of Carclew, 21 January 2013.

[58] Anna Held, ‘Being Independent’, Lowdown V.29.1, p18-21. Adelaide: Carclew, 2007.

[59] John Baylis, ‘Make it New?’, Lowdown V.28.3, p18-21. Adelaide: Carclew, 2006.

[60] Tony Mack, ‘Editorial’, Lowdown V.29.2, p2-3. Adelaide: Carclew, 2007.

2007-2009 History and Commentary

Lowdown and the New Millenium

2007-2009

A history and commentary by Tony Mack

2007-2009: A new Editor and a new Congress

Jane Gronow, Lowdown’s next Editor, brought considerable national experience and online expertise to the position. As National Project Officer for Community Arts SA she had been responsible for two national projects: Artwork Magazine, the national community cultural development (CCD) journal; and ccd.net, the national CCD website. As Project Manager of Applied Ideas, the position she held before coming to Lowdown, she had developed an online ecommerce portal linking designer-makers to manufacturers and markets.

Gronow had many attributes associated with Lowdown’s better Editors. Like Ian Chance, she came from a community arts background and had a national outlook. Like Belinda MacQueen, she had an infectious sense of humour and her gregarious nature made her a natural networker. And while, like Jo Shearer, she would place great emphasis on the visual appeal of the magazine and take production standards to a new high, it would not be at the expense of content. Lowdown featured some of its most insightful and comprehensive policy articles during her tenure, into subjects such as arts in the national curriculum, arts funding in Queensland and New South Wales, and the development, implementation and effect of the Make it New? restructuring of the funding policies of the Australia Council’s Theatre Board.

Gronow produced two strong focus issues during the rest of 2007. Her first issue explored the place of young people in the Australian music industry[1], featuring events and organisations such as: the NSW Government youth entertainment initiative, Indent; Tetrafide Percussion’s Advanced Performance Program in WA; the Sound Circles project in Cairns; Carclew’s Off The Couch program in SA; the Victorian Government’s Freeza program empowering young people to deliver their own music gigs throughout the State; Canberra Youth Music; and the Sydney Youth Orchestra.

This issue also announced that there had finally been a response to the crisis in theatre that Lowdown had been profiling. The Australian Government was committing $19.5 million over four years for small to medium-sized performing arts companies, ‘constituting an annual increase of more than 60%’[2].

In the October issue the focus was on emerging artist and innovation. Finegan Kruckemeyer profiled Frank Newman’s radically innovative experiment in puppetry and animation, Explosion Therapy, produced by Tasmania’s Terrapin Puppet Theatre. In the ACT, emerging theatre artists were profiled in the Canberra Youth Theatres Ensemble program. And in this issue Lowdown would provide the first media coverage of the ASSITEJ 2008 Congress Next Generation program, which would bring generational change to world youth arts in the coming years, sparking Next Generation programs and events in every continent and helping to launch the international careers of artists like Australian playwright (and Lowdown writer) Finegan Kruckemeyer.

Gronow faced a number of challenges throughout 2007. Assistant Editor Anna Held had been lured to a position at the Edinburgh Festival in the UK and Bridget Briscoe, who had been in charge of advertising, marketing and design, was headhunted by an Adelaide advertising firm. Carclew’s designer Yannick Bowe was brought in to design the magazine for the rest of 2007 and the first issue of 2008, while Gronow used the staffing changes as an opportunity to rework Lowdown’s staffing structure and production processes.

By April 2008 the new team was in place, just in time for the Congress in May. Samantha Ryan was the new Assistant Editor and design was outsourced to Irene Previn. The immediate result was a bumper 68-page April issue in colour, packed with content, superbly designed and with great visual appeal. As a Lowdown/Australia Council initiative, this was distributed at the ASSITEJ World Congress with a sister publication, The Lowdown Guide: Australian Performance for Young Audiences. With a focus in this guide on tour-ready Australian performances for young people, the magazine had created a new Lowdown Guide format that could be used in future to profile specific areas of youth arts, either at a state or national level.

Once again, an ASSITEJ World Congress in Adelaide would have a dramatic effect on Australian and world youth arts, and once again Lowdown was on hand to cover it. The June 2008 issue featured 16 pages of reviews and commentary on ASSITEJ 2008, the 16th World Congress and Performing Arts Festival for Young People[3].

With a program of 33 productions, two conferences, twelve forums, three Playwright Slams and numerous other workshops, activities and events, the Congress attracted thousands of national and international artists, artsworkers and delegates, including 480 registered delegates from 47 countries. Large delegations from Korea, Japan and the USA underlined the fact that the Asia Pacific relationships begun by Michael FitzGerald in the late 1980s had not only survived, but thrived.

The Congress worked with the ASSITEJ Executive Committee to respond to two major international themes – a focus on the next generation of practitioners and the rise to prominence of theatre for the very young – and these were prominently featured in the program. The Next Generation project was a ten-day artistic leadership program running throughout the Congress, with 23 people from18 countries on six continents taking part. Each had been nominated by their peers around the world as a new leader in their field. Artistic Director Jason Cross programmed five productions that sat within the Theatre for the Very Young category: Surprise from Dschungel Wein in Austria; Christine Johnston’s Fluff from Queensland; Cat and The Green Sheep from Windmill Performing Arts in South Australia; and HalliHallå from Sweden’s Teater Tre.

As promised in Adelaide’s 2005 bid document, Asia Pacific and indigenous productions also had a prominent focus. Six works fell into the Asia Pacific category, three coming from island cultures. Play BST’s Gamoonjang Baby was based on the traditional songs and dances of Jeju Island, off Korea’s coast. The Voyage (or Michi-nu-sura, from Kijimuna Dance & Music Troupe) showcased the traditional dance and music of the Okinawa Islands. From New Zealand company The Conch came Vula, a beautiful visual theatre performance exploring the sensual and spiritual relationship between Pacific Island women and the sea. Korea also had a second inclusion, the powerful Korea/UK collaboration of The Bridge, and two works from South East Asia were included. Thailand’s Never Say Die (or Mahajanok, from Makhampom Theatre Group) combined traditional Thai dance-drama with contemporary politics and physical theatre, while Chaos in Unison from Hands Percussion Team in Malaysia used traditional Malaysian drums in a contemporary performance that explored the relationship between the drum and drummer.

The festival program, however, was only part of a greater aim – to create opportunities for each delegate to establish intense connections with other delegates, artists, academics and theatre practitioners and be challenged, inspired and entertained by the ideas and practices of different cultures. This was evident in the structuring of the human environment of the Congress, an environment that facilitated people coming together not only in the formal sessions and as audience members, but in the free time, spaces and presentations of the entire ten days.

Apart from the networking and tours created, the legacy of the Congress continues to influence world youth arts. As mentioned, the Next Generation program model first covered by Lowdown has since been replicated at events and festivals around the world, and consolidated a place in international arts events for emerging and independent artists. The Congress also featured the first International Theatre for Young Audiences Research Network (or ITYARN) Conference, with subsequent conferences and forums in four continents since. The Playwright Slams, featuring 22 writers from 15 countries reading excerpts from their work, were expanded in the 2011 Congress in Copenhagen and Malmo, becoming the first official event of a new world playwrights network, Write Local. Play Global. This was founded by Kim Peter Kovac, Tony Mack and Deirdre Kelly Lavrakas in 2011 and in 2013 had over 460 members in 43 countries. With its website, writelocalplayglobal.org, and its Slams, Shorts and Sparks programs worldwide, the network promotes and supports writing for young audiences and is the official ASSITEJ playwrights network.